Sintesi

During the Knights’ period, slaves were an important element of the economy. Many of them were housed in the Prigione degli Schiavi or Gran Prigione, commonly known as the Bagno degli Schiavi. Although the name of this building makes explicit reference to slaves, the prison was not only meant as a compound for captives. Besides the Order’s slaves, at the bagno also resided the privately-owned slaves against payment of a scudo per month. However, irrespective of their religion, within the Slaves’ Prison were imprisoned even the male free-subjects. Under the Knights, the Gran Prigione assumed control of the various social groups that constituted the urban population of the harbour area.The prison in Valletta was the principal compound of the Order’s harbour cities. It provided accommodation for about 900 inmates.Two chapels, dedicated to St John the Baptist and the Holy Cross, were found inside the prison. Besides the chapels for the Christians, there was also a mosque for the Muslim slaves.Several communal spaces were located at the prison including a tavern and shops for barbers and tailors. It is likely that these common areas were found around the prison’s courtyard and the public was permitted to enter. The courtyard of the Slaves’ Prison was one of several other public spaces in which there was a market, which was focused on products of the Levant. In fact, the Slaves’ Prison was one of the first buildings in Valletta to be supplied by running water after Grand Master Fra’ Alof de Wignacourt installed in 1615 an aqueduct providing water from the northern part of Malta to Valletta.

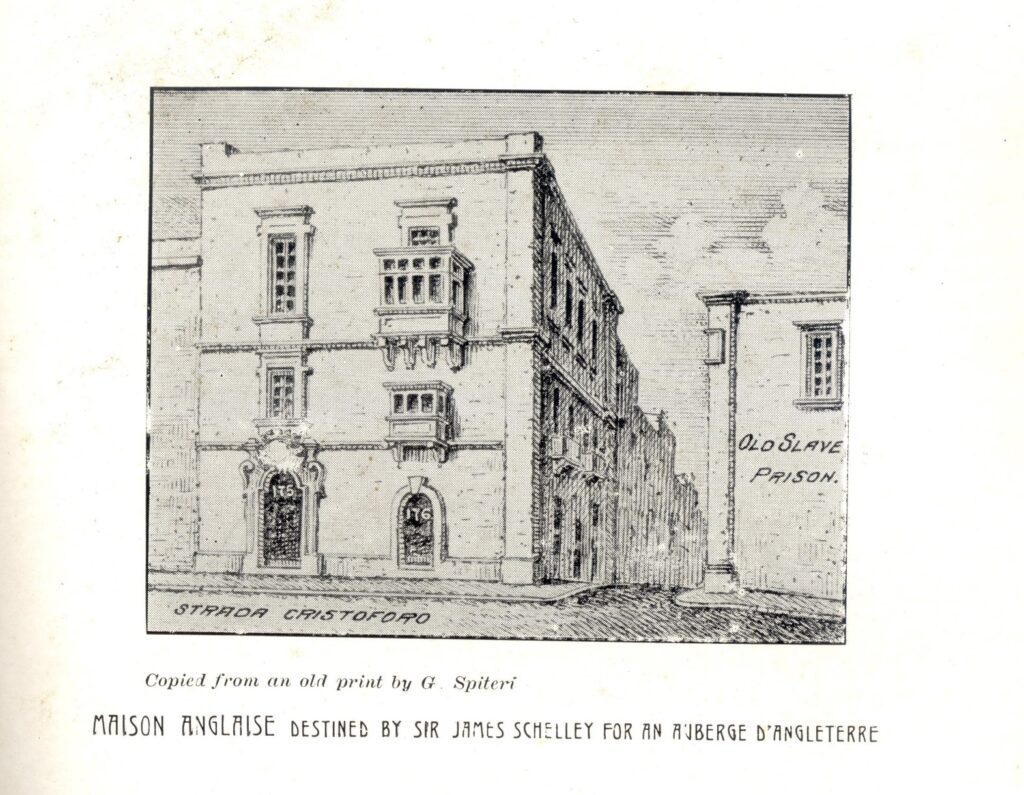

During the first years following the foundation of Valletta, the cavaliers of St John and St James on the land front were used to house slaves. Under Grand Master Fra’ Hugues Loubenx de Verdala (1581-95) a new site was constructed behind the bastion of St Christopher. It seems that the Slaves’ Prison was already completed by 1585. The architect of this building is not yet known, although Mahoney attributed its design to Girolamo Cassar (c. 1520 – c. 1592). The prison was erected on three-storeys and occupied an entire block bounded by St Christopher Street, St Ursula Street, East Street, and Wells Street. It was located directly opposite the Lower Barracca Gardens.

The building was severely damaged in the Second World War, and was entirely demolished in the postwar period to make way for a large and modern housing block.

Its plan was quadrilateral and a courtyard was found at the centre. The courtyard seems to have been directly accessed from the street. A 1633 plan of Valletta shows two entrances to the prison, one leading on St Ursula Street fronting and terminating St Dominic Street and another entrance at the opposite end on East Street. Other three plans of the Slaves’ Prison originate to the early 19th century. Andrè Zammit (2009, 203) points out that these three plans, which were published by Wettinger in 2002 are the same as those he had lent him from his private archive. Furthermore, Zammit (2009, 205) clarified that these plans were probably drawn at an early date than the year 1830 as given by Wettinger (2002, 96-8). Besides cartographic evidence, the layout and features of the prison could be deduced from written sources. The prison was described as a huge old edifice in a late 17th century account by the French traveller, Jouvin de Rochefort (1640-1710). Rochefort’s description provides few more details on the architecture of the courtyard, which space is said to have had porticoes surrounding it and behind these were four corridors that went around this open space. Other contemporary sources also mention that there was a fountain at the centre of the courtyard. Such plan reflects that of the market located behind the grand master’s palace erected in the mid- to the second half of the 17th century. Another fountain was also found inside the mosque, which Rochefort described as being carved in the form of a drinking-through.The building extended beyond St Dominic Street almost reaching the boundaries of the Sacra Infermeria. The internal layout of the prison is little-known, however few of its spaces could be described from different written sources. Surrounding the courtyard were several single-prisoner cells and a dormitory which was fitted within the great wards. The dormitory accommodated between 18 to 34 prisoners, and was organized into two sections above each other by means of a loft. Every inmate had a tiny patch where to keep personal items and rough bedding. Some form of distinction was given to the rais, the masters and captains of captured ships, who were accommodated in separate quarters. On St Christopher Street’s end, a long room extended from one corner of the block to the other. On the three other ends of the building, several moderately-sized rooms opened onto the courtyard. Along St Ursula Street were four large rooms, while six smaller ones defined the Grand Harbour’s end of the prison. All rooms were accessed directly from the courtyard and had no interconnecting doors. Onto Wells Street end, a series of interconnected rooms were possibly used by the prison’s staff.

- Bonello, Giovanni, Histories of Malta: Figments and fragments, Malta 2000, p. 48.

- Bonnici, Alexander, Superstitions in Malta. Towards the Middle of the Seventeenth Century in the light of the Inquisition Trials, Melita Historica, Vol. 4, No. 3, Malta 1966, 145-183.

- Borg-Muscat, David, Prison life in Malta in the 18th century. Valletta’s Gran Prigione, Storja, Malta 2001, 42-51.

- Cassar, Paul, A medical service for slaves in Malta during the rule of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, Medical History, Vol. 12, Issue 3, Malta 1968

- Cutajar, Nathaniel and Mevrick Spiteri, Ottoman coffee cups from 18th century Birgu and Valletta, Tesserae, Issue 8, Malta 2019, 38-45

- De Boisgelin, Louis, Ancient and Modern Malta, London 1805, p. 319.

- Wettinger, Godfrey, Slavery in the Islands of Malta and Gozo ca. 1000-1812, Malta 2002, p. 85-98, 123-5.